Critical Thinking

...The Longest-Running Critical Thinking Conference in the World

Entirely Online with Real-Time Study Groups

Registration Closed

Click titles for session descriptions . . .

Intensive Workshops

Critical Thinking in Education

Critical Thinking in Business and Government

Critical Thinking in Personal Life and Society

September 18, 2020

1:00 p.m. - 7:00 p.m. Eastern Time (10:00 a.m. - 4:00 p.m. Pacific)

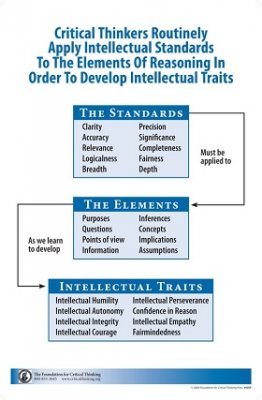

The pre-conference will focus on the fundamentals of critical thinking. This session will lay the foundation for all other conference sessions. It will introduce you to some of the most basic understandings in critical thinking – namely, how to analyze thinking, how to assess it, and how to develop and foster intellectual virtues or dispositions.  One conceptual set that we will focus on is the elements of reasoning, or parts of thinking. The elements or parts of reasoning are those essential dimensions of reasoning that are present whenever and wherever reasoning occurs —independent of whether we are reasoning well or poorly. For instance we use assumptions in our reasoning; we pursue purposes; there are implications and consequences of our thinking, and so forth. Working together, the elements of reasoning shape reasoning and provide a general logic to the use of thought. They are presupposed in every subject, discipline, and domain of human thought.

One conceptual set that we will focus on is the elements of reasoning, or parts of thinking. The elements or parts of reasoning are those essential dimensions of reasoning that are present whenever and wherever reasoning occurs —independent of whether we are reasoning well or poorly. For instance we use assumptions in our reasoning; we pursue purposes; there are implications and consequences of our thinking, and so forth. Working together, the elements of reasoning shape reasoning and provide a general logic to the use of thought. They are presupposed in every subject, discipline, and domain of human thought.

A second conceptual set we will focus on is universal intellectual standards. One of the fundamentals of critical thinking is the ability to assess reasoning. To be skilled at assessment requires that we consistently take apart thinking and examine the parts with respect to standards of quality. We do this using criteria based on clarity, accuracy, precision, relevance, depth, breadth, logicalness, and significance. Critical thinkers recognize that, whenever they are reasoning, they reason to some purpose (element of reasoning). Implicit goals are built into their thought processes. But their reasoning is improved when they are clear (intellectual standard) about that purpose or goal. Similarly, to reason well, they need to know that, consciously or unconsciously, they  are using relevant (intellectual standard) information (element of reasoning) in their thinking. Furthermore, their reasoning improves if and when they make sure the information they are using is accurate (intellectual standard).

are using relevant (intellectual standard) information (element of reasoning) in their thinking. Furthermore, their reasoning improves if and when they make sure the information they are using is accurate (intellectual standard).

A third conceptual set in critical thinking is intellectual virtues or traits. Critical thinking does not entail merely intellectual skills. It is a way of orienting oneself in the world. It is a way of approaching problems that differs significantly from that which is typical in human life. People may have critical thinking skills and abilities, and yet still be unable to enter viewpoints with which they disagree. They may have critical thinking abilities, and yet still be unable to analyze the beliefs that guide their behavior. They may have critical thinking abilities, and yet be unable to distinguish between what they know and what they don’t know, to persevere through difficult problems and issues, to think fairmindedly, to stand alone against the crowd. Thus, in developing as a thinker, and fostering critical thinking abilities in others, it is important to develop intellectual virtues – the virtues of fairmindedness, intellectual humility, intellectual perseverance, intellectual courage, intellectual empathy, intellectual autonomy, intellectual integrity, and confidence in reason.

This session is designed for new conference attendees, as well as returning registrants who appreciate the importance of continual practice in the fundamentals of critical thinking for their own advancement.

September 25, 2020

1:00 p.m. - 7:00 p.m. Eastern Time (10:00 a.m. - 4:00 p.m. Pacific)

This session addresses the same concepts and tools explicated in the Higher Education session above, but it contextualizes them to K-12 education.

October 2, 2020

1:00 p.m. - 7:00 p.m. Eastern Time (10:00 a.m. - 4:00 p.m. Pacific)

Educated persons skillfully, routinely engage in substantive writing. Substantive writing consists of focusing on a subject worth writing about, and then saying something  worth saying about it. It also enhances our reading: whenever we read to acquire knowledge, we should write to take ownership of what we are reading. Furthermore, just as we must write to gain an initial understanding of a subject's primary ideas, so also must we write to begin thinking within the subject as a whole and making connections between ideas within and beyond it.

worth saying about it. It also enhances our reading: whenever we read to acquire knowledge, we should write to take ownership of what we are reading. Furthermore, just as we must write to gain an initial understanding of a subject's primary ideas, so also must we write to begin thinking within the subject as a whole and making connections between ideas within and beyond it.

Quite remarkably, many students have never written in a substantive way. Instead, they have developed the habit of getting by – often while receiving passing or even high marks from their instructors – with superficial and impressionistic writing which only obscures the purpose of writing itself. The lack of connection between the writing assignments students complete and the way in which writing can be used to enrich their learning and lives can leave them resistant to, or dreadful of, their next assigned paper.

This session will explore ways of developing student abilities in substantive writing, through the tools of critical thinking, as a means for fulfilling, deep learning, which should also be enjoyable as an interrelated set of skills.

Throughout the schooling process (K- higher ed), students are continually assessed using numerous tests and measurements, focused on every subject in which they take classes. However, students are rarely taught the importance of internalizing intellectual standards for assessing their own thinking – standards such as clarity, precision, accuracy, relevance, depth, breadth, logic, fairness, and sufficiency. These standards are essential to reasoning well within any field of study or domain of human thought. In this session, you will be introduced to these standards, and to methods for helping students learn how to actively use intellectual standards in assessing their own reasoning as they reason through content. We will also focus on the importance of using these standards to judge the reasoning of others.

In some disciplines, the experts rarely disagree; in others, disagreement is common. The reason for this is found in the kinds of questions they ask and the nature of what they study. Mathematics and the physical and biological sciences primarily fall into the first category. They mainly study phenomena that behave consistently under predictable conditions and they pose questions that can be expressed clearly and precisely, with virtually complete expert agreement. The disciplines dealing with humans, in contrast—all the social disciplines, the Arts, and the Humanities—primarily fall into the second category. What they study is often unpredictably variable.

This session will focus on helping students learn to reason through multilogical problems and issues within the disciplines. Participants will formulate multilogical questions within their disciplines and consider how skilled thinkers from different perspectives would reason through those questions. Participants will also think through how to engage students in the same process.

Bringing critical thinking into the high school classroom entails understanding the concepts and principles embedded in reasoning and then applying those concepts throughout the curriculum. It means developing powerful strategies that emerge when we begin to understand critical thinking. In this session we will focus on strategies for engaging the intellect at the high school level. These strategies are powerful and useful, because each is a way to get students actively engaged in thinking about what they are trying to learn. Each represents a shift of responsibility for learning from the teacher to the student. These strategies suggest ways to get your students to do the hard work of learning.

Critical thinking, deeply understood, provides a rich set of concepts that enable us to think our way through any subject or discipline, through any problem or issue. With a substantive concept of critical thinking clearly in mind, we begin to see the pressing need for a staff development program that fosters critical thinking within and across the curriculum. As we come to understand a substantive concept of critical thinking, we are able to follow-out its implications in designing a professional development program. By means of it, we begin to see important implications for every part of the institution –redesigning policies, providing administrative support for critical thinking, rethinking the mission, coordinating and providing faculty workshops in critical thinking, redefining faculty as learners as well as teachers, assessing students, faculty, and the institution as a whole in terms of critical thinking abilities and traits. We realize that robust critical thinking should be the guiding force for all of our educational efforts. This session presents a professional development model that can provide the vehicle for deep change across the curriculum, across the institution.

To acquire substantive knowledge, students need: 1) engagement in the active construction of knowledge and 2) constructive feedback for that construction. This session will focus on the second half of this need: the reception of constructive feedback. Students can learn how to improve their own thinking and that of others by learning simple techniques for giving constructive feedback. This session will focus on how to get students to give constructive feedback that helps others as they expand their knowledge and insight by getting constructive feedback from those others. Through this process, students can learn how to help other students think more clearly, accurately, precisely, relevantly, deeply, broadly, logically, and fairly (as they learn how to do so themselves).

Students learn content within any subject only to the extent that they learn to think through the subject using their own thinking. But they can’t just use their own thinking. They have to use skilled, disciplined, reasonable, rational thinking - in other words, critical thinking. To do this, they need consistent practice over time in taking important ideas and following out the implications of those ideas, in integrating ideas, and in questioning them when it makes sense to. They need consistent practice in applying intellectual standards to thought as they reason through problems and issues within academic disciplines. They need to start with essential intellectual standards, and to apply those over and over again to problems and issues as they think through content. In short, they can’t just learn the theory of critical thinking in an abstract way. Rather, they need to learn the theory in relation to practice in applying it (that is, applying it to learning and ultimately to every domain of human life). This session focuses on taking the foundational theory of critical thinking and helping students internalize it through practice in thinking through content.

To study well and learn any subject is to learn how to think with discipline in that subject. It is to learn to think within its logic, to:

To become a skilled learner is to become a self-directed, self-disciplined, self-monitored, and self-corrective thinker who has given assent to rigorous standards of thought and to mindful command of their use. Skilled learning of a discipline requires that one respect the power of it, as well as its, and one’s own, historical and human limitations. This session will offer strategies for helping students begin to take learning seriously.

This session focuses on a number of instructional ideas that are based on the idea that substantive teaching and learning can occur only when students take ownership of the most basic principles and concepts of the subject. These strategies are rooted in a vision of instruction implied by critical thinking, and in an analysis of the weaknesses typically found in most traditional didactic lecture/quiz/test formats of instruction. This session focuses on some basic instructional strategies that foster the development of student thinking, and strategies that require students to think actively within the concepts and principles of the subject.

One of the main goals of instruction is to help the student internalize the most basic concepts in the subject and to learn to think through questions in everyday life using those concepts. Critical thinking in biology is biological thinking. Critical thinking in anatomy is anatomical thinking. Critical thinking in literature is thinking the way a knowledgeable, sensitive, reasonable reader thinks about literature. A discipline is more than a body of information. It is a distinctive way (or set of ways) of looking at the world and thinking through a set of questions about it. It is systematic and has a logic of its own. In this session, participants will think thought the logic of a discipline of their choosing. They will also focus on teaching the logic of their discipline so students internalize the way of thinking inherent in the subject as a life-long acquisition.

Classic literature, when well chosen, captures the highest-level standards in literature. One way of deepening our understanding of critical thinking and its role in history is to routinely and systematically interrelate explicit critical thinking concepts and principles with transformative ideas developed by deep thinkers throughout history. Many students have no real understanding of the important and essential ideas that have been developed by significant thinkers in history, nor do most students know how to access or assess classic texts. In this session, we will consider the works of a few distinguished thinkers throughout history and discuss how these thoughts interrelate, as well as how they connect with the conceptual tools in critical thinking.

One of the most important skills in critical thinking is that of evaluating information. However, those in business and government need a rich perspective on evidence-based decision making; this begins with the important recognition that information and fact, or information and verification, are not the same thing. It requires also the important recognition that not everything presented as fact is true. It is essential to comprehend that the prestige or setting in which information is asserted, as well as the prestige of the person or group asserting it, is no guarantee of accuracy or reliability. Consider the following helpful maxim: An educated person is one who has learned that information almost always turns out to be incomplete at best, and very often is false, misleading, fictitious, mendacious, etc.

Careful professionals, skilled in evidence-based decision making at a high level, use a wide variety of safeguards in making decisions based on actual evidence – not merely on information asserted to be true. It is not possible to learn these safeguards separately from an actual study of the best thinking within the disciplines. It is possible, however, to develop a healthy skepticism about information in general, and especially about information presented in support of a belief that serves the vested interests of a person or group. This skepticism is applied by regularly asking key questions about information presented to us:

These questions, both singly and as a group, represent no panacea. They do not prevent us from making mistakes. But, used with good judgment, they help us lower the number of mistakes we make in assessing information.

In this session, we will explore a rich conception of evidence-based decision making, which is highly relevant to your work in business or government.

Can we deal with incessant, accelerating change and complexity without revolutionizing our thinking? Traditionally, our thinking has been designed for routine, habit, and rule-bound procedures. Not long ago, we learned how to do our jobs, and then we used what we learned over and over in performing those jobs. But the problems we now face, and will increasingly face, require a radically different form of thinking: thinking that is more complex, more adaptable, and more sensitive to divergent points of view. The world in which we now live requires that we continually relearn, that we routinely rethink our decisions, and that we regularly reevaluate the way we work and live. In short, there is a new world facing us – one in which the power of the mind to command itself, to regularly engage in self-analysis, will increasingly determine the quality of our work, the quality of our lives, and perhaps our very survival.

As you work through this session, you will begin to understand some of the most fundamental concepts critical thinkers use on a daily basis, for it is through analyzing thinking that critical thinking occurs. To analyze thinking, we must be able to take it apart and scrutinize how we are using each part. When we clearly understand the parts of thinking (or elements of reasoning), and we begin to use them explicitly in our thinking on a daily basis, the quality of our work significantly improves.

This session will help business, government, and education leaders:

Reasoning through issues and problems with skill and competence is essential to functioning at a high level in business and government. This requires understanding and internalizing fundamental critical thinking concepts and principles and using these concepts and principles routinely throughout the workday, as well as in planning for the future of the company or governmental agency. One set of critical thinking concepts and principles essential to competent reasoning comes from universal intellectual standards such as clarity, precision, accuracy, relevance, depth, breadth, logic, fairness, and sufficiency. In this session, we will introduce and elaborate these standards; participants will apply them within the context of business or government.

Most people are trapped in their beliefs. They use ideas in their thinking that they are unaware of and have never examined for quality. They have developed a world view which influences much of their behavior, but of which they have little or no understanding. They are using assumptions accumulated throughout their lives which lead to their inferences and conclusions, but which they themselves have little or no awareness of. They are trapped in egocentric narrow-mindedness and sociocentric vested interests.

In short, the mind can be trapped in unexamined beliefs, concepts, assumptions, and world- views, or it can be freed through intellectual self-discipline and cultivation. This session will focus on the multiple ways that critical thinking can help us (and our students) become more independent, and hence more free, in our thinking. It will focus on understanding the dual problem of egocentric and sociocentric thinking as barriers to liberating the mind. Dr. Elder will utilize material from her new book: Liberating the Mind: Overcoming Sociocentric and Egocentric Thinking (Rowman & Littlefield, 2020).

Educated persons are skilled at, and routinely engage in, close reading. When reading, they seek to learn from texts. They generate questions as they read, and they seek answers to those questions by reading widely and skillfully. In short, they seek to become better educated through reading. They do this through the process of intellectually interacting with the texts they read, while they are reading. They come to understand what they read by paraphrasing, elaborating, exemplifying, and illustrating it. They make connections as they read. They evaluate as they read. They bring important ideas into their thinking as they read.

Our earth is our home. Our home is under attack from many pollutants spewed into the atmosphere and into our oceans by our species. A growing number of people across the globe are increasingly anxious as to how to deal with the pressing problems thrust upon us through the warming of the earth and the polluting of our oceans. In this session, we will focus on what we can do, from the point of view of critical thinking, to combat climate change and other environmental problems related to climate change.

In the prerecorded Keynote, the Senior Fellows of the Foundation for Critical Thinking will provide an overview of the fundamentals of the Paul-Elder Framework for Critical Thinking.

While this presentation will be a great refresher for returning participants, it will be especially important for new attendees to view the Keynote before moving on to other Focal Presentations and Live Discussions.

Most people who begin to learn the tools of critical thinking stop learning before they have a chance to really internalize, and therefore use, these intellectual instruments. However, a few go on to take the theory and application of critical thinking to deeper levels. This session is designed for conference attendees who have worked with us before, at previous conferences or at their institutions in professional development, and are ready to go further through pursuing answers to their own questions.

Thinking is driven by questions. The best thinkers generate and pursue deep questions that lead them to fruitful ways of thinking and higher ways of living. This session, led by an international authority on critical thinking, will focus on your deeper questions. Dr. Elder will help you develop improved lines of inquiry so you can explore, at a more advanced level, the concepts and principles embedded in a robust conception of critical thinking. Be prepared to articulate and pursue your important questions.

Registration Closed