|

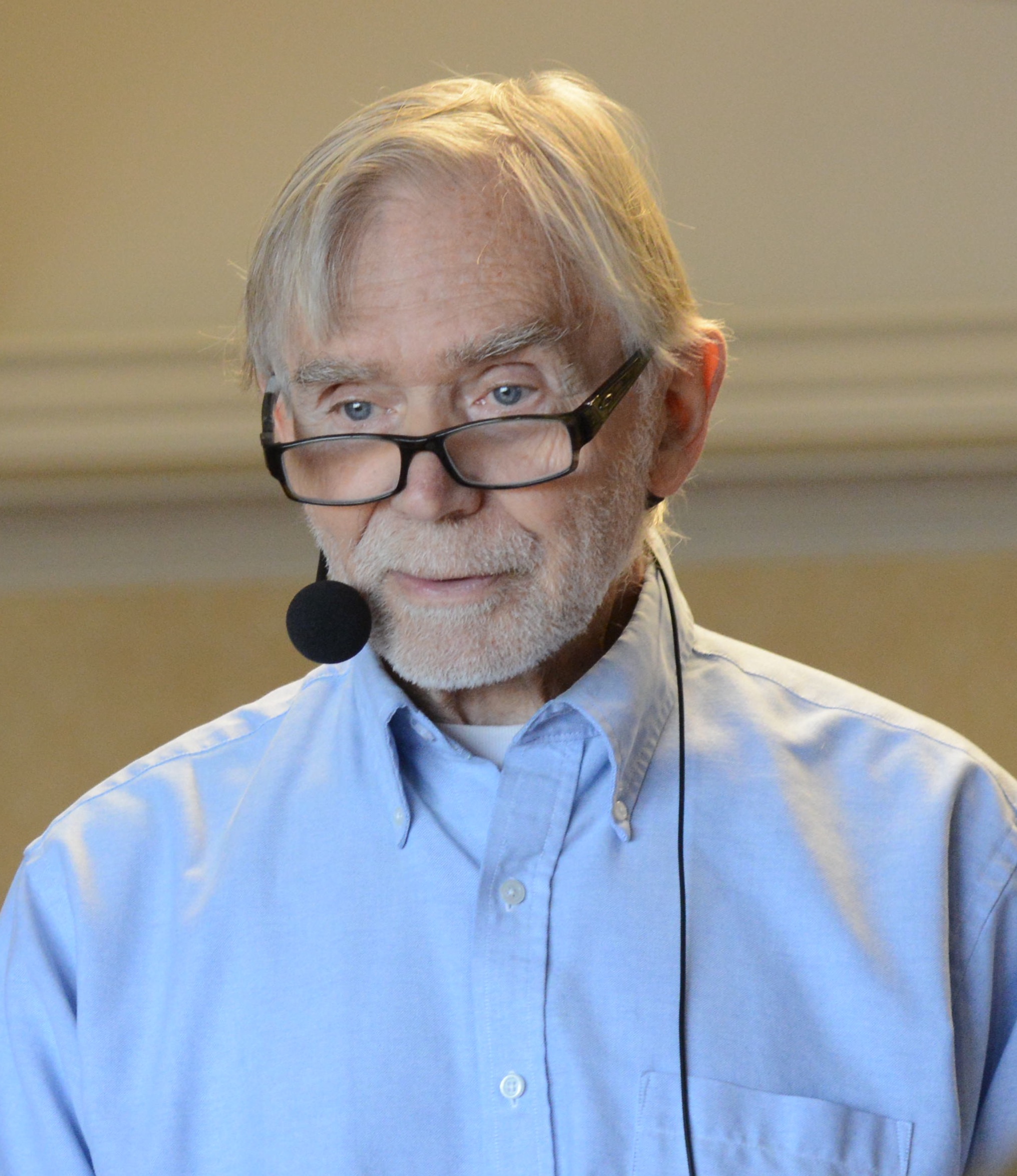

Dr. Richard Paul

Dr. Richard Paul is a distinguished leader in the international critical thinking movement. He is Director of Research at the Center for Critical Thinking, the Chair of the National Council for Excellence in Critical Thinking, and author of over 200 articles and seven books on critical thinking. Dr. Paul has given hundreds of workshops on critical thinking and made a series of eight critical thinking video programs for PBS. His views on critical thinking have been canvassed in the New York Times, Education Week, The Chronicle of Higher Education, American Teacher, Educational Leadership, Newsweek, U.S. News & World Report, and Reader's Digest.

Dr. Linda Elder

Dr. Linda Elder is an educational psychologist and a prominent authority on critical thinking. She is President of the Foundation for Critical Thinking and Executive Director of the Center for Critical Thinking. Dr. Elder has taught psychology and critical thinking at the college level and has given presentations to more than 20,000 educators at all levels. She has coauthored four books and twenty Thinker's Guides on critical thinking. Her views have been canvassed in the Times Higher Education, the Christian Science Monitor, and on National Public Radio. |

Dr. Gerald NosichDr. Gerald Nosich is an authority on critical thinking. He has given more than 150 national and international workshops on critical thinking. He has worked with the U.S. Department of Education on a project for the National Assessment of Higher Order Thinking skills, has served as the Assistant Director of the Center for Critical Thinking, and has been featured as a Noted Scholar at the University of British Columbia. He is Professor of Philosophy at Buffalo State College in New York. He is the author of two books, including Learning to Think Things Through.

Mr. Rush CosgroveMr. Rush Cosgrove is Historian for the Foundation for Critical Thinking and is engaged in research for a PhD at the University of Cambridge. He holds Masters degrees from both the University of Oxford, New College and the University of Cambridge, Darwin College. He has conducted research on critical thinking and the Oxford Tutorial, and is currently conducting research on the Paulian Framework for critical thinking as contextualized at a major U.S. research university. He conducts workshops in critical thinking for both faculty and students in English as well as Spanish.

Mr. Brian Barnes Brian Barnes has taught Critical Thinking courses for seven years at the university level. He has earned grants from Hanover College, the James Randi Education Foundation, and the University of Louisville focused on developing critical thinking in everyday life. He holds a Masters degree in Philosophy and is a PhD candidate at the University of Louisville, which fosters the Paulian Approach to critical thinking across the curriculum.

ADDITIONAL MAIN CONFERENCE PRESENTERS |

|

Gary Meegan

Gary Meegan is Chair of Theology at Junipero Serra High School in San Mateo, California. He has taught both in public and private school settings, from Kindergarten through twelfth grade. He has presented sessions on critical thinking to the American Men's Association, the American Academy of Religion, the California Association of Teachers of English and to elementary and secondary schools. This is his fourth year to present at the International Conference on Critical Thinking and Education Reform. His doctoral work involves online education in critical thinking for teachers and students.

Laura Ramey Laura Ramey

Laura Ramey teaches theology, the history of Christianity, and social justice at Serra High School in San Mateo. She has incorporated critical thinking in her high school classes for the last five years. She holds Masters degrees in business and theology and is currently completing research for her EdD at the University of San Francisco. With partner teacher Gary Meegan, Laura has presented papers and workshops on the practical aspects of teaching critical thinking for the Foundation and Center for Critical Thinking, the American Academy of Religion, and the National Catholic Educational Association. This is Laura's fourth year presenting at the international Conference on Critical Thinking Reform. |

|

|

|

|

Laura Ramey

Laura Ramey