Conference Presenter Information

FOUNDATION for CRITICAL THINKING FELLOWS |

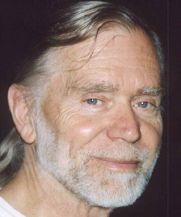

| Dr. Richard Paul

Dr. Richard Paul is a distinguished leader in the international critical thinking movement. He is Director of Research at the Center for Critical Thinking, the Chair of the National Council for Excellence in Critical Thinking, and author of over 200 articles and seven books on critical thinking. Dr. Paul has given hundreds of workshops on critical thinking and made a series of eight critical thinking video programs for PBS. His views on critical thinking have been canvassed in New York Times, Education Week, The Chronicle of Higher Education, American Teacher, Educational Leadership, Newsweek, U.S. News and World Report, and Reader's Digest. |

| Dr. Linda Elder

Dr. Linda Elder is an educational psychologist and a prominent authority on critical thinking. She is President of the Foundation for Critical Thinking and Executive Director of the Center for Critical Thinking. Dr. Elder has taught psychology and critical thinking at the college level and has given presentations to more than 20,000 educators at all levels. She has coauthored four books and 20 thinker's guides on critical thinking. Her views have been canvassed in the Times Higher Education, the Christian Science Monitor, and on National Public Radio. |

Dr. Gerald Nosich Dr. Gerald Nosich

Dr. Gerald Nosich is an authority on critical thinking. He has given more than 150 national and

international workshops on critical thinking. He has worked with the U.S. Department of

Education on a project for the National Assessment of Higher Order Thinking skills, has served

as the Assistant Director of the Center for Critical Thinking, and been featured as a Noted

Scholar at the University of British Columbia. He is Professor of Philosophy at Buffalo State

College in New York. He is the author of two books including Learning to Thinking Things

Through.

Mr. Rush Cosgrove Mr. Rush Cosgrove

Mr. Rush Cosgrove is Historian for the Foundation for Critical Thinking and is engaged in

research for a PhD at the University of Cambridge. He holds Masters degrees from both the University of Oxford, New College and the University of Cambridge, Darwin College. He has conducted research on critical thinking and the Oxford Tutorial and is current conducting research on the Paulian Framework for critical thinking as contextualized at the University of Louisville. He conducts workshops in critical thinking for both faculty and students, in both English and Spanish. ADDITIONAL MAIN CONFERENCE PRESENTERS |

| Dr. Patty Payette

Patty Payette is the executive director of “Ideas to Action,” the Quality Enhancement Plan at the University of Louisville and is associate director of UofL’s Delphi Center for Teaching and Learning. Patty has more than ten years of experience in higher education faculty development, instructional/curriculum design, and training and development for instructors and administrators. Dr. Payette has designed and delivered dozens of workshops on teaching and learning topics, including sessions on critical thinking across the curriculum. She consults with schools and colleges nationally on the design and implementation of critical thinking initiatives. She has designed and taught undergraduates courses at Michigan State University—where she earned her PhD in 2001--and the University of Michigan-Flint. Her publications include numerous essays, articles, and book reviews on a variety of higher education topics, including articles appearing in the National Teaching and Learning Forum; Academic Leader; and The Chronicle of Higher Education.

|

Introducing at this year's conference…

The Bertrand Russell Distinguished Scholars Critical Thinking Lecture Series

This new feature of the conference will highlight the work and thinking of distinguished thinkers within subjects, fields, disciplines or about specific topics or issues. This year's scholars include Michael Shermer, William Robinson, and Ethan Watters. All conference participants are invited to these lectures.

Dr. Michael Shermer

Dr. Michael Shermer is the Publisher of Skeptic magazine, a monthly columnist for Scientific American, and author of many books including Why People Believe Weird Things. He was a college professor for 20 years, and has appeared on such shows as The Colbert Report, 20/20, Dateline, Charlie Rose, and Larry King Live. Dr. Shermer was the co-host and co-producer of the 13-hour Family Channel television series, Exploring the Unknown.

Ethan Watters

Ethan Watters is the author of Crazy Like Us: The Globalization of the American Psyche and coauthor of Making Monsters, an indictment of the recovered memory movement. A frequent contributor to The New York Times Magazine, Discover, Men’s Journal, Details, Wired, and PRI's This American Life, he has appeared on such national media as Good Morning America, Talk of the Nation, and CNN. His work has been featured in the Best American Science and Nature Writing series.

William I. Robinson William I. Robinson is professor of sociology, global studies, and Latin American studies at the University of California at Santa Barbara. He is a scholar-activist who participates in social justice movements in Latin America and the United States. Among his seven books are A Theory of Global Capitalism (2004) and Latin America and Global Capitalism (2008). His web page is www.soc.ucsb.edu/faculty/robinson.

|

|